It’s the summer of 2017. Jasmine and Zane (then 5) go to Denmark to visit my sister’s family, who spend their summers in Copenhagen. I stay home with little Kalani (then 2), because he won’t appreciate the 12 hour flight, the Rugbrød (rye bread), or the pickled herring. It’s so much fun that Jasmine decides to return with both boys, now that Kalani is older and able to get around by himself. The summer road trip is on!

This tickles me with excitement. Imagine a 44-year-old man, rolling around on the floor, giggling like a Tickle Me Elmo doll. Kind of creepy, now that I think about it, but you get the idea. Almost two full weeks dedicated to an epic climbing trip! Joey and I begin to put together a tick list. The list culminates with us conquering the mighty summit of Mt. Dana, a serious back country objective we’ve been dreaming about for the last few years. The route that continues to elude us. We will need to get in shape and do this strategically, if Dana is to go down.

Adios, family. They are off to Denmark and Sweden as I hit the road for Bend

Both of us were motivated. I felt like this would be our opportunity to push our trad game up a notch. That being harder free climbing on gear, which is a very different beast than running up some crimpy top rope in the gym. I’m not sure where the line is drawn between easy punting and legit climbing, but I feel like we’ve been flirting with it for the last couple of years. Joey was expecting his first child in a month from now, so he had his own reasons to savor a long climbing trip.

During the months leading up to our summer trip, we trained aggressively. Well, at least Joey was training hard. He was ARC’ing in the gym, hangboarding to strengthen his fingers, and climbing at Smith to dial in his lead head. I found ways to get stronger, too. It was a questionable program built on the consumption of carne asada burritos and pizza, which would become “training weight” that I would miraculously shed right before the trip. It sort of worked, actually.

So, in early July, I dropped the family off at LAX and within minutes, I was traveling on Interstate 5, gunning for Oregon. I managed to make it to Sacramento, that night. I got some restless sleep on the side of the road and, fueled by Circle K coffee, made it to Bend the next day. The trip had become a reality.

I focused on a single, critical objective during the drive to Bend. Nothing else mattered, and I spent hours contemplating how I would feel, once I accomplished the goal. I had to eat the spicy fried chicken at Fricken Faco. It had been 6 weeks since I was there on my last visit, a fun trip where we climbed at Trout Creek and Smith and a secret crag that Joey and Eric have been developing. We finished the days off with fried chicken, fries, and cold beer. That would be my last meal of indulgence. July was nearly upon us and I had to lose 10 pounds, if I was going to be in shape for the 3rd Pillar. I had been fasting or dieting every day for 6 weeks, getting in shape. My reward would be fried chicken bites tossed in spicy sauce, and the best fries in the world.

Joey had to finish up some work before leaving, so I hung out with Groomer and Bodhi, and made some sourdough bread. The next day, we hit the road for Lover’s Leap, a popular granite crag near Lake Tahoe. The idea was to get dialed in on granite cracks, since Joey had spent the entire summer climbing on Smith’s volcanic tuff, and to sample some of the local classics like Bear’s Reach and The Line.

We decided to approach Lover’s as a low pressure warm up, but it quickly became apparent that something was off. Joey’s lead head, so strong and dialed the last time I was in Bend, was cooked like a goose. He’d been dealing with a variety of heavy issues; the impending arrival of his first child, his mom’s health, and work stress. It was understandable, and I realized that I would need to quash any of my own trepidation and find ways to increase our stoke and motivation. Climbing is all about finding the right head space and appreciating the intensity of the moment. When this becomes a struggle, it ceases to be fun at all.

We warmed up on some easier multi-pitch lines, which I thought were really fun. We were able to tick a couple of multi-pitch routes a day, with the short approach and easy walk-off. The granite felt comfortable and reminded us of Tahquitz, where we honed our chops early on. I wasn’t thrilled with the loose flakes, and there were times where I felt like I might pull the outer layer of rock away from the mountain. Granite cliffs like this undergo a constant erosion called exfoliation, where the outer layer of rock peels off in thin flakes, like the skin of an onion. This process creates wonderful holds and cracks to grab onto, but you don’t want to be there when the layer you’re clinging to decides to let go. Some of the flakes would flex and bend as we weighted them, so we climbed carefully and deliberately.

By the third day, we were feeling more comfortable and decided to try a harder line called the Sinbad-Herbert. Just to the right of Surrealistic Pillar, one of the most popular classics at The Leap, the first pitch of the route follows a super aesthetic, overhanging crack on interesting corrugated rock. We wanted to climb The Pillar, but it was always mobbed with people, and we never woke up early enough to get our ticket. Sinbad looked even more attractive, though, and sees less traffic due to the stouter grade. Joey climbed the first pitch in good style, utilizing a mix of secure jams and long reaches to the plentiful face holds. I lowered him off and then sent it myself, using a slightly different approach that involved more stemming and body English in the awkward corner. I have notoriously long arms and a good reach, but Joey is 6’7″ and it’s always interesting to see how differently we approach a climb. Fist bumps and smiles after, things were looking better and I hoped the nerves were behind us. We were getting ready to move on to Tuolumne, and our heads needed to be straight.

Before leaving Tahoe, we decided to tackle one more route, and arguably one of the classics in the entire State of California. Royal Robbins famously called it, “the best pitch at The Leap, and one of the ten best pitches I have done anywhere.” Paul Piana claimed it was “the best 5.9 I’ve ever done.” The Line is a 400 foot long, nearly continuous thin crack that runs down the middle of the main wall. Our running joke is that we’re working on becoming “5.10 all day” climbers, which means that we want to confidently climb any 5.10 route, regardless of style or length, comfortably and safely. We are not there yet, but we are getting close. The 5.9 grade is in our wheelhouse; just spicy enough to get the blood flowing, without too much drama or difficulty. I took the first pitch, which involved some unprotected face climbing to reach the start of the crack. I was feeling confident and made good time, clipping some fixed gear that was stuck in the crack. Everything was going great, until I reached the belay ledge, which appeared to be a chossy collection of rotten flakes that were in the process of falling off the mountain. I wasn’t thrilled with the notion of belaying from the ledge, but the only other option would be to continue up and build a hanging belay from the crack, which would be terribly uncomfortable. So, I placed no fewer than 4 pieces, equalized as best as possible and divided up between two or three suspect flakes, should one of them decide to blow. Then I adjusted the length of the rope and tethered myself in, squishing my butt and thigh firmly into a notch. A lot of unlikely events would have to happen to rip me off this belay ledge, and I knew Joey wasn’t going to fall, in any case.

We decided to link the 2nd and 3rd pitches, which meant that Joey was in for one of the longest and most sustained pitches of his life. He would have to negotiate more thin crack, some crumbly face, and then pull an intimidating roof about 200 feet above us. On many climbs, a route will wander over features and overlaps, and it’s hard to grasp how high or exposed you really are. On The Line, it was a straight shot from the top to the ground, with a small visor-shaped roof that one needs to surmount to reach the plateau above. Joey looked nervous, upset, and unhappy. I don’t think we talked much at the belay. We exchanged gear and I muttered some words of encouragement. I think he might have told me that he wasn’t up for it, and wondered aloud if I might be willing to take the lead. Just feeling me out, as both of us have done in the past. This is one of the great things about an established partnership, since we are able to read each other’s body language and mood, and know just how much to push each other. I was riding a bit of a high, and felt bummed that he wasn’t enjoying the day in the same way. I told him I’d take the pitch if he wanted, but encouraged him to go for it, because he would regret giving it up. We were hanging there together, staring up at the rock, and experiencing some very different emotions. I’m not sure what, or who, he was thinking about. But it was my job to get him into a better head space, and give him a safe belay.

Joey made it to the top clean, and he let out some whoops as he pulled the roof. The gear was pretty good and there were nice jugs that appeared right where he needed them. That being said, pulling a roof when you’re 200 feet out from the belay isn’t for the faint of heart and it was a new experience. It was super exposed and committing, and I felt so proud of him for facing the challenge, in spite of his mood. Once on top, we were all smiles and he was a totally different person. This guy was definitely on a roller coaster of emotions.

We celebrated with some pizza and beer in town, and began the drive to Tuolumne. We passed a baby rattler on the way back to the car, which made me think of my boys, who are real snake aficionados.

It wasn’t clear how we would spend the remainder of the trip. With only a few days to go, I was starting to feel antsy and I wanted to capitalize on whatever time we had left. I felt like we were finally starting to build some momentum, and it was now or never if we were going to get some harder climbs done. On the other hand, maybe it would be best to slow down and relax, and just enjoy ourselves. During the drive, we discussed many of the same old topics (whether we were ready for Dana) and we tossed around the idea of backpacking over Kearsarge Pass to climb Charlotte Dome. We talked about climbing some of the longer classics on Mt. Russell, but iffy weather and obtaining a permit would be a problem. We settled on a mellow scramble up Tenaya Peak; a long and easy route, where we would continue to practice simul-climbing techniques.

We managed to get the same campsite as previous years (G13/14), which has come to feel like home whenever we’re in Tuolumne. We’ve spent so many fun nights here, it felt great. We drove over to inspect the NW face of Tenaya, with plans to climb it the next day. Unfortunately, a huge snow patch (the size of a football field) was still sitting on the middle of the route. Below the patch of snow, we saw long ribbons of shiny, wet rock. Climbing through here would be problematic, and if the snow happened to release while we were on the route, it would be potentially dangerous. Oh well, Tenaya wasn’t going anywhere and we decided to save it for a future trip. This is when we started discussing Mt. Conness, another moderate classic that we’d avoided due to the long approach and commitment involved. We weren’t really prepared for a night in the back country, but after taking stock of our supplies we came to the conclusion that it would be reasonable to do as an overnight, which would be much, much easier than a car-to-car venture. The route up Conness would be the longest technical climb we’ve ever done. Rated at only 5.6 (and much of it is much easier than that) it’s listed as being 10 pitches and 1,500 feet. It starts above treeline and tops out at 12,349 feet, which means thin air and unpredictable weather. I don’t think we’d ever done a Grade IV climb before, and while all this might seem trivial to a seasoned mountaineer/alpine climber, it was a step forward for us and we took it fairly seriously. All that being said, we weren’t really nervous or unprepared – the climbing itself would be easy, and having just done Prusik Peak car-to-car in a day, we felt pretty casual about it. The biggest unknown would be simul-climbing so many pitches of technical rock, and the weather.

One is able to catch a glimpse of Mt. Conness from Tuolumne Meadows, if you know where to look. A giant, gleaming white mountain that sits imposed over the surrounding terrain, it actually looks kinda chossy from afar. But Peter Croft calls it one of his favorites, so we bought a couple of thin foam pads and packed up our gear. We would hike up to the watershed below Young Lake in the afternoon, bivy at the base of the route, and then climb it the following day. The weather report looked so-so, and we had a small window before the risk of afternoon thunderstorms would become too great. Basically, we had one day to get in there and do it, or call the whole thing off. We decided to carry a very light alpine rack, so we would be able to move as quickly as possible. In this sort of terrain, weight slows you down, and speed keeps you safe (to an extent).

I’ve spent a lot of time backpacking in the High Sierra, so I felt pretty confident that we’d have a good time. Joey expressed some concern about bears and other critters that might visit us in the night, so I regaled him with some fun stories of the ursine kind. We obtained permits and hiked up to Young Lake on a very nice trail, and then headed cross-country over rougher terrain, heading north towards Conness, which we could see through the trees. As we got closer, it started to dawn on me that we were about to climb a huge fucking mountain. This was a multi-day objective that would require a whole range of back country skills. I was absolutely loving it. My personal journey to get here started 30 years ago, on my first backpacking trips into the Sierra. Then all the long days in the mountains with Steve and Lopez in my 20’s and 30’s, a bunch of solo adventures in pursuit of photography, and finally the step into roped free climbing, which started almost 20 years ago. To combine all these passions and have them culminate in the successful summit of a mountain via a technical route, would be a real accomplishment and something to be proud of.

We found a somewhat flat area of sand to set up camp, which consisted of a cheap plastic tarp strung between two trees. If it should rain that night, at least we wouldn’t be soaked. The mosquitoes were out in force, so we layered up and tried our best to keep them at bay. I don’t recall what we ate for dinner, but it was probably cold and bland. I started to feel an intense amount of solitude and my mood worsened, no doubt because I was worried about the next day. The weather was really on my mind, and I didn’t want to get stuck in a storm. Joey could tell that I didn’t feel great, and I am sure he was dealing with some of the same thoughts. I hiked a bit north to inspect the final approach to the climb, and I built some cairns to mark the location of our campsite.

Neither of us slept well that night; a combination of the altitude, our nerves, and the rock hard ground. I lied on my side, getting maybe 30 minutes of sleep, and would wake up with a numb arm or hip, and do it all over again. When the sun finally rose, I felt relieved. It was time to move.

The final approach was beautiful, passing through an alpine meadow laced with bubbling streams and small patches of snow. We eventually had to scramble up a loose talus field to reach the start of the climb, where we switched to our rock shoes and roped up.

We decided to climb on just one of my twin ropes, which we used when we simul-climbed Matthes Crest last year. On Conness, we would only use one of the thin ropes, but doubled over itself and 30 meters long, so that we would be able to stay in easy communication range. This worked out pretty well, and it was easier to manage the excess line during the climb. Joey volunteered to take the first pitch, which put me in the enviable position of being tied into the bottom end of the rope. If he fell, he would yank me up, and depending on his position, it might not be that bad. If I fell, it would yank him down, in all likelihood ripping him off the rock and sending us both for a ride. In reality, it was imperative that neither of us fall, because we were going to be moving fast and running it out, and help was a long ways away. We both carried belay devices and would stop to employ their use, over the trickiest sections.

As we started up, we scanned the sky for any signs of inclement weather. There were some friendly little clouds above us, and more ominous looking clouds to the south. Puffy clouds this early in the morning was a pretty bad sign. The weather report put the chances of thunderstorms at 20%, and we felt confident that we could summit and get down before they would become a problem. It was still nerve wracking, though, and as we simuled up the first couple of pitches, the uncertainty about the weather weighed on both of us.

The climbing was straightforward and easy. We were looking at a handful of pitches, no harder than 5.6, with no real route-finding issues. We ascended a featured ramp up the lower section of the mountain, at which point we would reach the main ridge, and follow that to the top. I don’t recall exactly, but I don’t think we had a strategy planned for the upper section, which was mostly 4th class (with some occasional short sections of 5th). We would figure it out when we reached it.

The simul-climbing, we have both come to agree in hindsight, sucked. We certainly moved fast, no question about it. But running it out with a wishy-washy belay was pretty nerve-wracking, and it wasn’t fun. Whenever one of us would encounter a tricky section, we would slow down and place a piece, the follower would give a proper belay, and then we would continue. I think we swapped leads and tagged gear 2 or 3 times, as we ascended the first few hundred feet of the route. It was nice to be climbing with such a light rack, though. Eventually, I topped out the end of the sustained 5th class and brought Joey up, as the clouds were getting thicker and some drops of rain fell began to fall. Oh shit.

Mt. Conness was the highest peak for miles, which meant our brightly colored, helmeted heads were also some of the highest things for miles. The thought of lightning terrified me, even more than the idea of trying to climb on wet rock. The clouds were whipping by quickly above us, and we could see thunderheads off in the distance. It never really rained, just light drops here and there, but it was a not-so-subtle warning: get to the top and down as quickly and safely as possible.

And there lies the conundrum that all alpine climbers eventually face. Moving slowly, methodically, and safely isn’t always safe. When climbing in this environment, there are other factors to consider. We were forced to consider them. We had reached the top of the technical climbing and knew that the rest of the route would be more of a scramble. On one hand, it seemed insane to untie from the rope when we were only halfway up the ridge. On the other, it would be stupid not to. Even if we continued to simul-climb, it would take us three times as long to reach the summit.

So, with very sober awareness of what we were about to do, we unroped and Joey coiled our line on his back. I felt a strange sense of relief that, at the very least, if one of us were to fall, the other would be ok. I took the lead and after a few minutes, I settled into a nice rhythm, and remarkably, I began to enjoy myself. I was still worried about the weather, but as we moved higher up the ridge, I could tell that we were close to the summit and that we would probably be fine. We were moving lightning fast, no pun intended. I was actually enjoying the exposure and I passed over the last technical moves without even realizing it, such was my enthusiasm. I wouldn’t go as far as to say we were free soloing, because the terrain was so easy it was more like an exposed scramble, but I was definitely in the zone and moving with a fluid speed, efficiently and having fun. I’m not sure Joey was experiencing the same positive feelings that I was, judging from the look on his face.

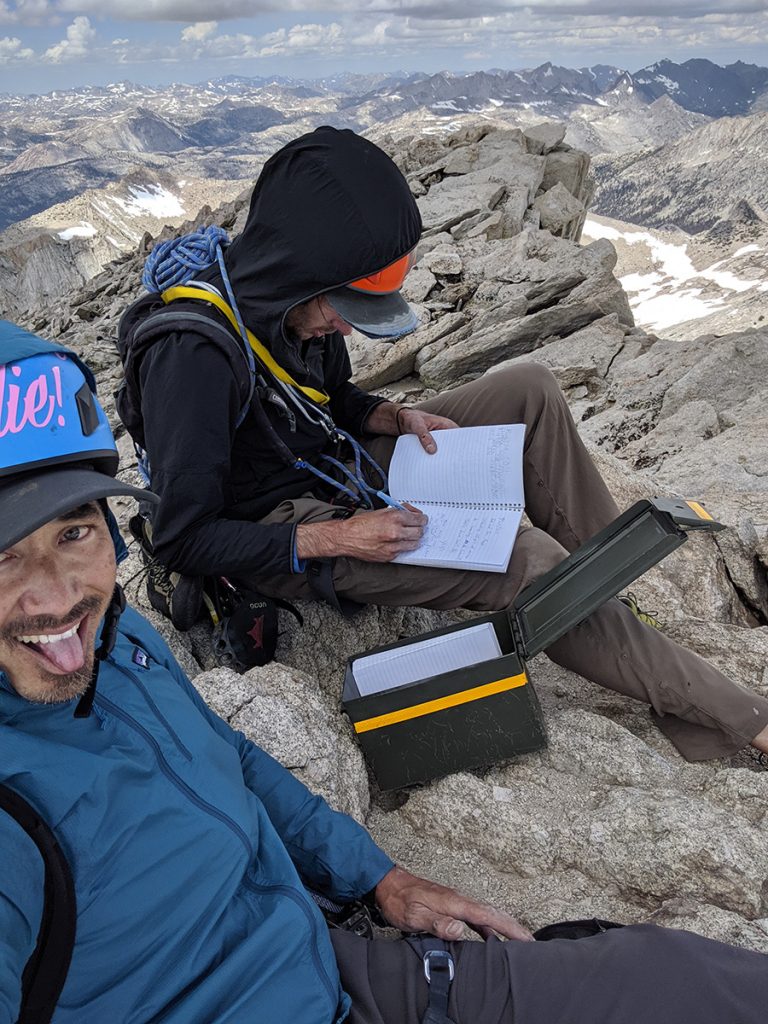

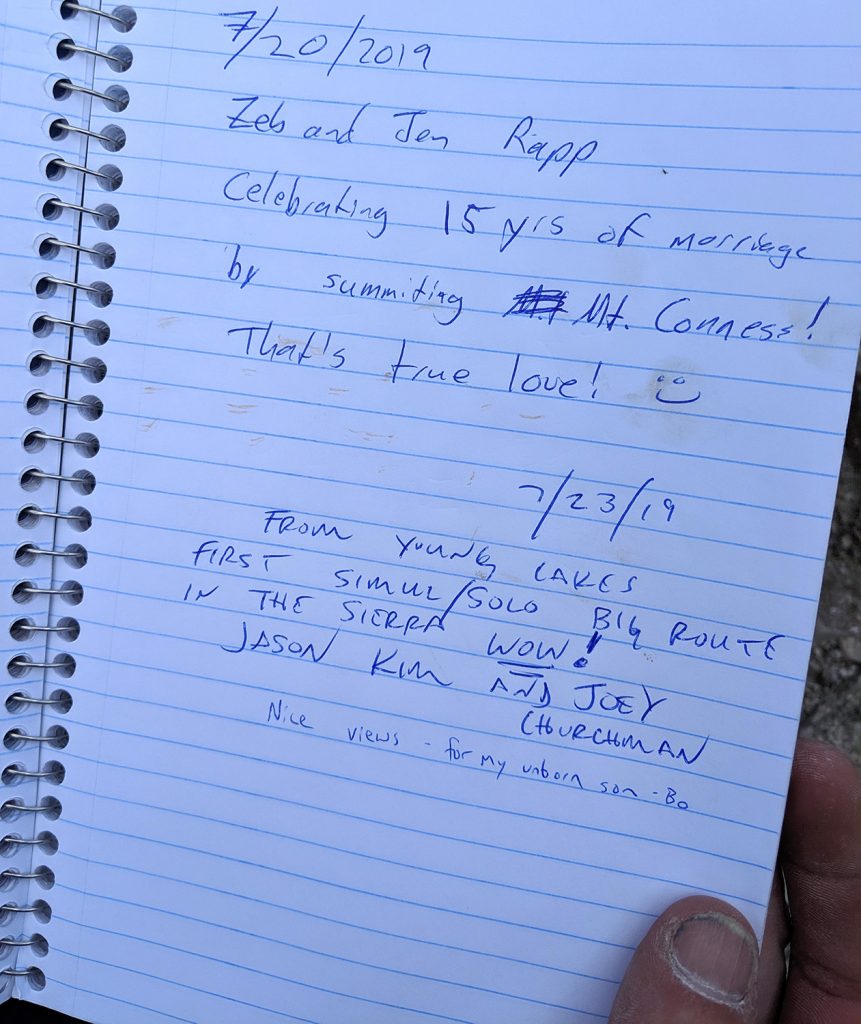

We reached the summit of Mt. Conness in just 3 hours, which is really an accomplishment (for us). That’s 1,500 feet of vertical climbing, at altitude, in less time than we’ve spent on much shorter routes. We signed the summit register and drank some water, and then we walked off in search of the descent gully, which would take some time.

We hoofed it back to the car that afternoon. The hike was enjoyable and mostly downhill, and we talked about our favorite foods and fatherhood. Joey’s son Boden was due in a couple of months, and I could tell the birth was on his mind. We relaxed the rest of the day and made some tasty paella over the campfire.

Tuolumne Meadows is one our favorite places to climb, but we found ourselves lacking the motivation or enthusiasm to do much else the next day. We continued to discuss Dana as an option, but it was clear that we lacked the focus or determination to give the route a fair shot. I think we both agreed that it would be better to wait, until we’re confident in our abilities and stand a chance to have a good time. Plus, the snow level was a lot lower than expected, and just getting to the base of the route would pose some challenges, and the weather report was getting worse. We were making excuses, but that’s how it goes, and we were ok with it. We slept in the next morning, and then hiked over to Lamb Dome. I wanted to check out an interesting traverse route called On the Lamb and the finger crack Little Sheeba. I’ve always been drawn to thin crack climbs and most of my toughest and proudest sends have been on this style of route. Little Sheeba looked long and slick, but it would protect well. I decided to give it a shot, and I jumped on the route with full intention to send in style, even if that meant taking a giant whip.

Joey was quiet and a bit distracted. He seemed willing to go along with whatever I wanted, but I didn’t get the sense that he was enjoying himself at all. We didn’t talk much, as we went through the standard pre-climb routine (knot checks, etc.) and I started up the route. Once I got 20 feet off the ground, with a couple of solid pieces in place, my confidence grew and I committed myself fully to the task at hand. I wanted to get to the top clean, no falls or takes. The feet were slicker than I expected, and halfway up, I knew that I had my work cut out for me. I would find a so-so stance, get a good piece in, and then fire through a series of moves to the next rest, none of which were great. There were two or three moments when I was almost certain I was going to peel off, and I yelled down the standard, “Watch me!” to let Joey know that I was right at my limit. The route was surprisingly long, and after turning a bulge I could see that it wasn’t over. But I made my way up and then I was clipping the bolted anchor, and I let go a satisfied and exhausted scream. I had just onsighted a Tuolumne 10a, and I was damn proud of myself.

I lowered off and Joey tied in, intending to follow the route and clean the gear I had placed. He made it up about 1/3 of the way, but he was clearly in a bad head space. He was struggling on the moves and hung on the rope, and he looked upset. I didn’t know whether I should encourage him or just let him sort it out, and I think I mostly stayed silent. He wasn’t being thoughtful with his foot placement and wouldn’t commit to the painful finger locks, and his frustration was growing by the second. Suddenly, he started slapping the rock with his hands and he was screaming. Painful yells and curse words. It wasn’t the climb that was getting him down, it was something else. He was on the verge of melting down. No, the process had already begun and he was melting down.

I lowered him off and told him that I would clean the route, since it was possible to scramble up the backside to reach the anchor. He walked off into the trees silently, and I took my time retrieving our gear. It started raining, the sky was ugly and dark, and it was probably the lowest point in our 8-year climbing partnership. I wasn’t sure what he was going through or how he was feeling, but he wasn’t capable of climbing anything at that moment. It was pointless to be out there on the rock together, and he had to sort some things out in his head.

Thirty minutes later, he returned from his sabbatical and apologized for melting down. I know our partnership and friendship is one of the most important things in his life, and I imagine he felt upset and ashamed for losing it. I felt bad that it had gotten to that point. I tried making a joke to lighten the mood. I told him it wasn’t a big deal, and that we would just take some time to figure this shit out. And then he started getting emotional and he apologized for ruining the trip, and that’s when I became adamant that the trip was a success, and that he had better knock that shit off right then and there. Climbing together is one of the most satisfying and important things in my life, and we’ve intentionally put ourselves into some intense situations together. We do this as a team and when one of us has an off day or a bad moment, the other has always been there to lift the team up. I wanted Joey to know that the trip was a success, because we were learning something about ourselves, our limits, our worries and our fears. We’d just climbed Conness in good style, the day before. Nothing could take that away from us, and it was ok to get emotional. Whether it’s during the drive, or on the long approaches, we often talk about life and family and all manner of topics, and it forces us to reflect on everything that is important to us, and it’s during those moments that I appreciate life the most.

We got back to camp in the rain and I’m not sure what we did the rest of that day. The trip took an unexpected turn, but we had already gotten a lot of good climbing under our belts and it was time to drive south.

We spent the next day driving around Bishop and trying to figure out what to do. We had a bit more time, but the weather was bad and we were tired. We decided to check out an area called Cardinal Pinnacle, which turned out to be a bit of a fiasco. After scrambling up a loose talus field, it started raining and nothing looked terribly appealing. We watched as a team climbed the West Face of the formation, a route that we had considered. As the rain increased, they decided to bail, so we just stood there at the base, watching them. That’s when we heard one of them yell, “Rock! Rock!” and a chunk of granite the size of a small table came hurling down from above. It was eerie, watching this huge piece of rock just silently drop through the air. It exploded with a huge bang about 100 feet away from us. We threw our helmets back on and started skating down the loose talus, back to the car. That place gave me the spooks.

And so, that was it. We left Cardinal and spent the rest of the afternoon exploring Pine Creek Canyon just north of Bishop. The canyon is a popular sport crag, but it was relatively empty due to the cold, unpredictable weather. Joey’s mood was on the upswing again, and he led a challenging bolted route in good style, and I followed. We hiked around and looked at some options for a future trip, and then drove back down to Lone Pine, spending our final night in the Alabama Hills. Our trip had come to an end, and even though it didn’t work out exactly as expected, it was an amazing time and we learned quite a bit. We’ve come to the conclusion that simul-climbing isn’t worth the risk, but we know we can do it, if weather or darkness forces us to move fast. We’ve confirmed that long days in the mountains is where it’s at – the day on Conness was just a wonderful adventure for so many reasons. And we figured out a way to enjoy a serviceable California burrito, even when we’re far from home.