I met Justin in 2009, when his wife Cara began her uro-gyn fellowship with Jasmine at UCSD. He has ~20 years of climbing experience and is the reason that I got back into the sport. It’s been really helpful to learn from such an experienced mentor, and unfortunately the Grimes-Marquis family will be moving back to New York later this summer. I see a future trip out to the Gunks with Tom.

Back in the day, I mostly bouldered and climbed indoors, but Steve gave it up after injuring himself and lacking a reliable partner, so did I. Anyway, I met Justin and we started surfing and climbing together, and then our wives mysteriously became pregnant within 3 weeks of each other. Now we’re both doing the stay-at-home dad thing, so suffice to say, we have a lot in common.

With both wives out of town with our little ones, we had planned to do a surf trip to Baja. I thought it would be a crime if he didn’t get a chance to surf San Miguel or K58 before leaving San Diego. Unfortunately, the weather turned foul and we were looking at blown-out conditions. So, we decided to make a trip out to Joshua Tree instead. Justin secured a campsite at Jumbo Rocks on Friday afternoon and I met him there in the evening, arriving at 11 pm. It was snowing lightly and the wind was howling. As I pulled into the campsite, I saw that my REI Hobitat had just about broken free from its stakes and was lurching about like a demon-possessed fun house. This would turn out to be one of the worst nights of sleep, ever. The stakes kept pulling out of the soft sand and I ended up guying the fly out to my truck with climbing rope. Even then, the tent lunged back and forth and flapped like a maniac all night. Based on the way I felt the next morning, I’d be surprised if I slept more than an hour in total. It felt like someone was smacking me in the face with a broom all night. I saw a bunch of broken and mangled tents the next day, on our drive out of the campground.

It might have been the lack of sleep, or possibly a piece of sand in my eye, but my vision was somewhat blurry the next day. We woke up and ate a quick breakfast, and then decided to climb Mike’s Books (5.7+) on Justin’s recommendation. This is one of his favorites in Hidden Valley, and it did not disappoint. There are three ways to start the climb, and I attempted the “direct” version that is supposed to be 5.8. It felt like a 5.impossible in my sleep-deprived, blurry-eyed state, so I turned my attention to variation #2, which involved some easy slab climbing and a traverse over to the crack. What looked perfectly doable from the ground turned out to be a rather exposed and frightening proposition; a precarious stance about 12 feet off the ground, no pro, and some balanced friction moves around a sloping, no-holds corner. I was certain that I’d slip off and break both my ankles, and that wasn’t the way I wanted to start our trip. I downclimbed, cursed, and turned my attention to variation #3. A few committing stem moves and up I went. I was finally in the first “book” and I placed a solid purple camalot. The rest of the climb felt much easier, and I was able to practice my hand jam technique.

I should note; we climbed on Justin’s rack the entire trip, which is somewhat sparse when compared to the big wall mess that I have grown accustomed to carrying. He discouraged me from climbing with any more than necessary, and it made me a little nervous. When I got to the top of the first pitch, I had a #3 camalot and a few small TCU’s, along with an assortment of nuts. Looking around, I didn’t see any obvious anchor opportunities with such small gear. I placed the #3 in a big crack, and then equalized the cam with a platter-size horn that I had tied off with a sling. The horn looked bomber to me, but Justin commented that he didn’t like the fact that my anchor consisted of only 2 pieces (3 being the preferred minimum, unless your belay stance happens to include a mature pine). We looked around and he pointed out some thin cracks that I could have used, which were 20 feet back from the top of the climb, but certainly within reach. I had plenty of rope, and in retrospect, I could have done some creative rope work to build a more redundant anchor. It was a good lesson, and one of the reasons why it’s important to climb with someone who actually knows what he’s doing.

We rapped down from Mike’s Books and then drove out to the Wonderland of Rocks area, where Justin led Life’s a Bitch and Then You Marry One (5.7). If you’re wondering who it was that picked the route, no comment! Actually, it’s one of the climbs listed in the “60 Favorite Trad Climbs” book, so it was on our tick-list. I’m guessing that whoever put up the first ascent must have had some relationship issues.

The climb protected well and Justin tackled it without difficulty. Building the anchor was a little tricky, though. The route topped out on some rather blank rock, and the rap bolts were 12 feet off to the right. Justin built a four-piece directional using some small nuts and a tri-cam in a thin, awkward-looking crack, and then belayed me while anchored and hanging from the bolts. An ingenious solution and I’m not sure I would have thought of it. Another lesson learned.

We rapped down and then scrambled over to another climb nearby, a route our guidebook called Keystone Crack. Mountain Project lists it as an unnamed 5.6, so I’m not sure if it was the real Keystone Crack, but I led it, whatever it is. In fact, I’ll go ahead and name it Get Your Head Together and Climb Already, Crack. I had some issues with the start, which always seems to happen when the initial moves are unprotected and committing. I got about 8 feet off the ground, traversed up and right, and was faced with a committing move to a ledge, which looked like it would be the first opportunity to place some gear. I couldn’t commit, and I kept climbing up and back down, feeling it out. The traverse was sapping my confidence, because I could see myself popping off the little sidepulls that were holding me to the wall. I was getting really annoyed with myself, and I finally walked over to the right and just started climbing directly up the face, to avoid the traverse. The moves were harder, but it didn’t freak me out as much. The rest of the climb went well, and we finished up and called it a day.

We stopped in town for some supplies, which included a blanket of questionable origin. It was much colder than expected, and Justin’s sleeping bag wasn’t cutting it. We got a fire going and proceeded to swap stories, and judging by the number of empty bottles I collected the next morning, we must have had a good time.

The next morning, we hiked out to the Isles in the Sky formation, which we had scoped out the day before. Justin had his eye on a nasty-looking crack called Dolphin (5.7+). The late Art Morimitsu had the following to say about this route: “Friends don’t let friends climb Dolphin.”

The guidebook mentioned some 4th class scrambling to get to the base of the climb, but we arrived to find 50+ feet of solid 5th class. It’s possible there’s another way up, since we didn’t spend a ton of time looking for an alternative. We just ditched our packs, roped up, and Justin led a quick pitch that deposited us safely at the base of the route. Everything in Joshua Tree seems sandbagged to me. 5.7+ means 5.9 and a 3rd class downclimb might as well be an epic free solo.

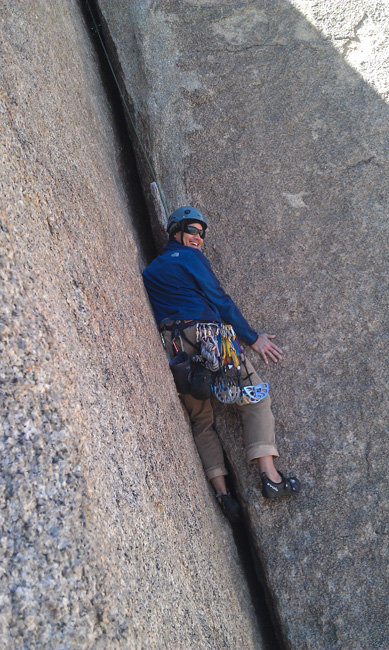

At first glance, Dolphin doesn’t look terribly intimidating. Sixty feet of straightforward hand crack splits the corner of a right-facing dihedral. It looked like it would protect well. Upon closer inspection, though, one notices that the crack slowly widens near the top, which would almost certainly be the crux. It was also cold and windy, and the route wasn’t getting any sun. Justin racked up with a couple of #4’s and his big #5 and #6, and got down to business.

I won’t say that he struggled, but I could tell that the initial section was harder than Justin expected. That left me wondering how I would do, since I have such limited crack climbing experience. Justin was stuffing hand and foot jams and I was taking mental notes; at least I would be on top rope. I could tell when he had reached the off-width section of the climb (really only the last 12 feet) because his upward progress came to a halt, and half his body was wedged firmly into the crack, as if the formation was trying to swallow him whole. This is when the grunting and cursing began. I couldn’t help but laugh, because it looked and sounded horrible. He placed the #6, which would be his final piece of pro until the top. Fifteen minutes later, he was still wedged in the same spot, having made some unsuccessful scouting trips into the nasty off-width above. He would climb up a few feet, become disgusted with what he saw, and then ooze back down to his last piece. There were a lot of guttural noises and scraping sounds. Finally, he mustered his courage and just went for it. It was ugly; the kind of thing young children shouldn’t be allowed to watch, but he made it to the top.

It was my turn, and I did alright – at first. I jammed up the crack and though it was insecure in places, I felt as if it was something that I could conceivably lead. That is, until I got near the top. The crack began to open up, and there weren’t many holds to be found. I thrust the entire left side of my body into the gradually flaring crack and used a random combination of chicken-wing armbars, knee and foot cams, and who knows what else to make upward progress. By the time I reached the top, I was huffing and puffing as if I had just sprinted a mile. My left ankle was rubbed raw and bleeding, and my fingertips were totally numb from scraping at the cold rock. It was a grueling affair, but fun, in a way.

Special thanks to Shane Norquist, who was climbing nearby and snapped these photos for us. Justin and I rapped down to the base and we decided that we had gotten our climbing fix. It was time for lunch at the Crossroads Cafe, and then back to San Diego. I was stoked when I found a brand spankin’ new BD Hoodwire quickdraw on the hike back to the trailhead.