It’s been nearly two weeks since we returned from Tuolumne Meadows, and my body is still in the final stages of recovery. My shoulders are peeling, my joints are stiff, and I’ve got scabs on the backs of my hands. It could be from the lack of sleep; Jasmine’s maternity leave has come to an end and I’m in charge of the early shift. For whatever reason, I still don’t feel 100%.

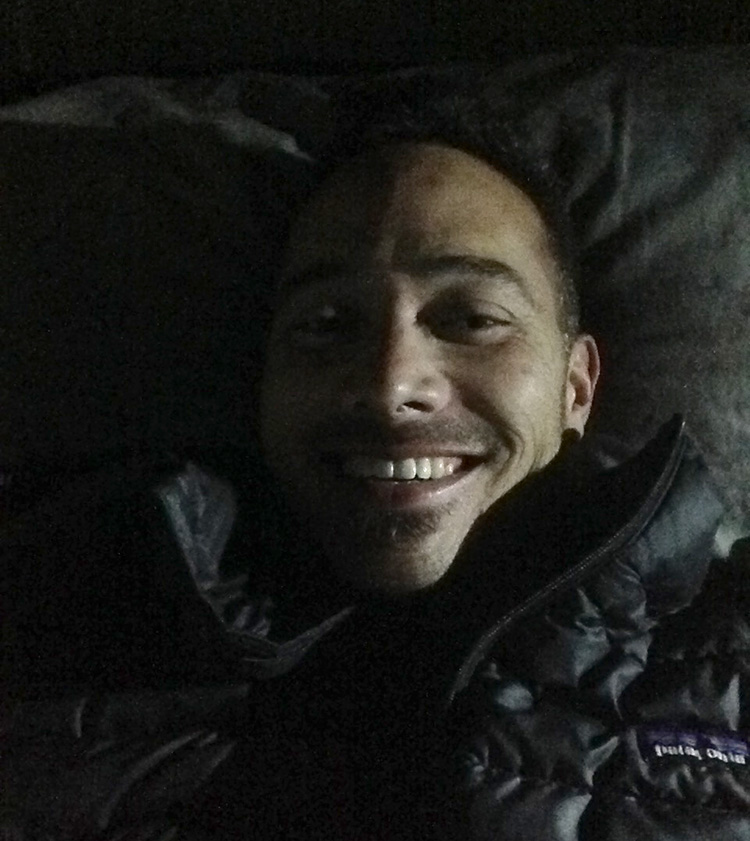

Joey and I arrived in Tuolumne on a Wednesday evening, just as the sun was setting. I’m turning 40 this month, and Jasmine generously gave me the go-ahead to spend 4 nights away from home, as my birthday present. Kalani is only 7 weeks old, so it was a truly wonderful gift! Joey called the ranger station during our drive up, and was told that Tuolumne had plenty of open sites; nothing to worry about. The ranger was either pulling our legs or a flood of campers arrived shortly thereafter, because the “campground full” sign greeted our arrival. Very disappointing. We drove to Porcupine Creek Campground – also full. Things were looking bleak, but we kept driving west on Hwy 120 towards the turnoff for Yosemite Creek Campground. Our phones didn’t work and we weren’t exactly sure where it was, and after 15 minutes of fruitless searching, I suggested a turn-around time of 9:00 pm. Our only other option would be in the other direction – back down Tioga Pass and out to Mono Lake, to camp on BLM land. The clock ticked forward and I was losing hope with each passing minute. Just as it ticked 9:00, we saw the turnoff! That had to be a sign, and we started down a rough dirt road. We passed a Japanese tourist carrying a surfboard in his rental car, which was strange (this being the middle of the night, on a forest dirt road). He told us he had come from California, when I asked about the board. Joey laughed and said, “We’re in California, dude.” We reached the campground 20 minutes later, quickly set up camp, and prepared for an early start the next morning. I collapsed onto my sleeping pad, grinning like a fool. Joey asked me what was going on. I was ecstatic at the thought of 6 hours sleep without the sound of a crying newborn! My birthday trip had officially begun, and I was overjoyed.

A few hours later, our alarms beeped and we began the 45 minute drive back to Tuolumne, in the dark. We parked at the trail head for Fairview Dome, and ours was the first car at the pullout, a bit after sunrise. As we racked our gear, a van pulled up and parked alongside us. A minute later, the door slid open and two climbers, fully decked out in gear and helmets, jumped out and literally start running up the trail. I guess they wanted to be first on the rock. They say they’re headed for the Regular Route, which gives me a sense of relief because it would make route-finding easier, since we will be right behind them. As it turns out, they climbed faster than a pair of snails (our pace) and they quickly disappeared out of view, once we were on the rock.

It took us 15 minutes to hike to the base of the dome. The sun was about to rise, and it was light enough to see just fine. I was able to catch glimpses of the monolithic rock above us, but it wasn’t until we broke through the trees that I got a real look at the route we intended to climb. Stepping out onto the slabs below the dome, I was stopped dead in my tracks as I looked up at the rock. To say that the dome was impressive and intimidating would be an understatement. It was huge. The face looked vertical, even though I knew it wasn’t. Fairview dwarfed any other crag or cliff that we’ve climbed before. It made the imposing Tahquitz look like a highball boulder problem.

The party ahead of us had already started up the first pitch, so we scrambled up to chat with the belayer. The leader was having some trouble about halfway up, and he was moving pretty slow. “There’s water in the crack!” I heard him shout down. The technical crux of the Regular Route comes in the very first pitch of climbing, which leads up a flared finger/hand crack to a tree, almost 200 feet high. When Joey and I had discussed the feasibility of this route, I felt confident knowing that the first pitch would be the hardest, and once over, we would simply “cruise” the rest. Well, reality was starting to set in, and there would be no cruising anything, we were about to discover. The 5.9 grade in Tuolumne is probably 10a or above, at most other climbing venues. Add some flowing water, and this moderate finger crack became my own personal Dawn Wall. I was screwed. So there was nothing left to do but tie into the rope, and find out what we were made of.

About halfway up the pitch, I had come to the conclusion that I hated climbing, and would never do it again. I hadn’t yet reached the wet section, and from what I could tell, I wasn’t even into the hardest part of the crack. The rock was slippery, glacier-polished granite. I searched in vain for tiny knobs or crystals to gain some purchase for my feet, but the texture of the rock was disturbingly smooth. The crack was a bit flared and my jams were tenuous at best. The party above was just finishing the pitch as I started up, and the second yelled up to his leader, “How did you make it up this wet part?!” Turns out, the leader had French-freed the toughest sections, pulling on gear to make upward progress. Oh, I am totally fucked, I thought to myself. I’d only tried that once before, and it was a mere 10 feet off the ground. It also meant that I’d be 100% dependent on the gear – if a piece blows, I am going for a ride.

But, we were only one rope-length up, and the gear was good. At worst, I knew we could do a single-line rap off the tree above, and bail if we really had to. I was totally prepared to leave my rope hanging off the first pitch of Fairview, and slither back to the car with my tail between my legs. My rope is old and needs replacing, I tried to rationalize to myself. I continued up, placing Joey’s 0.4 Camalot in the crack and inching higher, testing the next flared pocket to see if my fingers would fit. POP! My feet unexpectedly slipped off the rock and I was falling. Not far – it was more of a gradual “slipping down the rock” as the rope caught me but continued to stretch. Actually, it was Joey who caught me, and I am forever grateful that I have such a good belayer. It was a surprise that I didn’t see coming, and a bit of a shock. I’ve slipped a couple of other times on lead, but this would probably be my first real fall on gear, albeit a tiny one. I hung for a while, smiling down at Joey and feeling a sense of satisfaction that the theory behind our protection system actually worked.

At that point, I was roughly 100 feet into a 1,000 foot climb, I was feeling shaky and weak, and I was getting ready to bail. I looked down at Joey and yelled something along the lines of, “This really sucks, man.”

But I continued on, because facing these fears and overcoming them is one of the reasons we climb. I reached the wet section and knew that there was little hope of climbing it free. There was a steady trickle of icy water flowing down the crack. I had no designs to climb the pitch clean, by this point, and all I wanted was to make it safely to the tree. I started using cams and nuts to aid my way up the crack, hanging when needed, and by the time I reached the top, I was almost out of gear, at the end of our rope, and had just successfully completed an unplanned crash-course in aid climbing techniques. I was still thinking about bailing, but figured that I had to bring Joey up, for no other reason than to see the look on his face as he tackled the wet crack.

On long routes like this, most parties swing leads, meaning a pair of climbers take turns leading each pitch to the top. Once Joey reached the belay, we talked things over. It was still early in the day, and we had just finished the hardest part of the climb. It feels pretty lousy to bail off a route, and the relative comfort of our belay ledge quickly erased the horrors that felt so imminent, just minutes before. It was Joey’s lead, anyway, so I was starting to relax and made every effort to collect myself.

Unfortunately for me, his lead was over in about 10 minutes, only 30 feet higher, at the next ledge. He could have pushed higher, but we were following our topo and it would have introduced some undesirable unknowns if he had passed the ledge.

I reached the belay, we exchanged gear, and I was suddenly faced with another long, hard lead up an exposed corner. The pitch was rated 5.8, but now I carried the burden of knowing that Tuolumne 5.8 was another way of saying “your personal limit.” Furthermore, I knew that by striking out onto the 3rd pitch, we would be getting high enough that retreat by descent would become a difficult, if not impossible option. We hadn’t quite reached it yet, but there would soon come a point where the only way off the rock would be by topping out. That can be a frightening feeling, and it’s one of the differences between single-pitch cragging and the more serious business of tackling multi-pitch terrain in the alpine.

Let me be clear: I probably worry about this stuff too much. At the same time, it seems like many climbers downplay or ignore these risks altogether. An injury or accident (even a minor one) or bad weather can turn into a serious problem on multi-pitch terrain, and I don’t know many climbers who regularly practice self-rescue techniques or carry emergency bivy gear. I pride myself on being self-sufficient and prepared, and the last thing I want is to get myself into a predicament that requires a rescue (or worse).

I made it to the top of the third pitch in bad style. I went from mildly rattled, to borderline scared by the time I reached the next ledge. Near the top, I was running low on gear and had to run it out more than I would have liked, to save some pieces for the anchor. I was almost out of rope. I happily pulled on gear to make upward progress, whenever the opportunity presented itself. The last thing I wanted to do was take a fall and risk injury. I wasn’t enjoying the climbing at all and I was pretty certain that the entire trip was a huge mistake. By the time I reached the belay, I was a psychological and emotional mess. I was thinking about my wife and kids, which is something I often do just before a hard climb, but never have these thoughts crossed my mind during a climb. I wasn’t climbing in the zone, and the only thing I was focused on was my own fear, which was escalating out of control. Had this been a single-pitch route in Joshua Tree, I would have onsighted it easily. But given the circumstances, and my deteriorating mental state, it became the hardest pitch of climbing I’ve ever done. I was never in any real danger. But I really felt like I was slipping into oblivion.

I brought Joey up, and he admitted that he, too, was on the verge of a mental breakdown. Later, he told me that he considered selling all his gear and devoting the rest of his climbing life to bouldering. Screw this ropes business, this is for the birds. We shuddered at the thought of attempting El Capitan – three times higher than Fairview and a far more serious objective. What were we thinking??

I spend a lot of time online; reading about climbs and other people’s trip reports, blogs, etc. One of the things I’ve noticed is that few climbers talk openly about their fears and failures. Sure, climbers will write stuff like, “That pitch was super scary, I almost crapped my pants!” but seldom do they treat the subject with any real, honest talk about being genuinely scared and pulling through it. Let’s face it, you need to have a certain screw loose to constantly put yourself into these situations. It’s possible that I am just a huge whiner, trying my best to play in a sport of hardman champions. Joey and I talk about our fears all the time (maybe too much) and it’s one of the things I appreciate about him. He’s confident enough in himself, and honest, to talk about this stuff openly. I don’t like climbing with people who uphold a veil of nonchalance or false courage, which is usually a sign of ignorance or insecurity. I suspect that everyone gets really scared from time to time, but there seems to be a culture of wanting to be a hardman, that prevents many from talking about it. Well, in our case, we’re not climbing anything terribly difficult or groundbreaking, so it would be a short and boring blog if I didn’t fill these pages with stories of my personal horror shows on these classic moderates.

We were 3 pitches up (out of 12) and though the end was still a long ways off, we were making progress. Also, we knew that the climbing would be easier as we gained ground, and that was enough to stoke whatever fire, or stupidity, was fueling our drive for the summit. We swapped gear again, Joey unclipped from the anchor, and we plodded on. We were moving really slow, and had sadly become the gumbies that people warn others about on long routes like these. We were the reason those other climbers bolted out of their van and started running up the trail, because nothing is worse than getting caught behind a 30 foot motor home on a twisty mountain road. 400 feet below, I watched as a party hiked up to the base of the route, observed our progress for a while, and then left. No doubt because we were moving too slow. “Gumbies.” I imagined they must have muttered to themselves, as they walked away.

A gumby is a clueless climber, and something that no one aspires to be. It is to climbing what a kook is to surfing.

Damn it, I just had a powerful moment of self-realization.

We climbed a few more pitches of 5.7ish terrain that felt much harder than any 5.7 we’ve climbed before. Joey took a long, tough lead up a corner system and pulled some tricky moves through a roof, which I felt was pretty legit. I almost got shut down on a 5.6 ramp as we got passed by a pair of speed climbers who had already dispatched a harder route earlier in the day (this being their second time up and down from the top of the dome, which was just mind boggling to me). The climbing eased way off as we approached the summit, but I do remember some scary moments where I was either way run-out or forced to make exposed traverses with minimal protection. Many parties simul-climb the upper pitches on this route, and we had intended to do the same, but the thought of climbing without a solid belay seemed like a silly-stupid idea, at that point. This decision, of course, slowed us down even more.

One of the things I enjoy doing, whenever I reach one of Joey’s anchors, is to clove into the masterpoint (or even a single piece, if it’s bomber) and then throw all my weight backwards and onto the gear. Usually, a look of abject terror crosses over his face and he grabs at the rope, as if the anchor is going to explode from the rock. I guess I trust the gear more than he does. It’s a fun game.

Joey seemed to relax a bit, once we were within a pitch or two of the top. I think I caught him whistling a song, and part of me wanted to slap him. I was still very much on edge, because I was worried about getting off route and the sun was about to set. Had I known that Joey neglected to bring his headlamp, I would have been a basket case. But lo and behold, some 12 hours after we had started, I found myself leading up the 12th and final pitch. I pulled up and over a short, slabby headwall and onto the top of Fairview Dome, as big and flat as a football field. I was ecstatic, letting out whoops and hollers as I ran over to a little pine to bring Joey up. I felt such an intense sense of relief, and the view was breathtaking. I was too tired and frazzled to make much sense of what we had just accomplished, but I knew that it was something epic – the kind of thing I will tell my grand kids about. Joey reached the top a few minutes later, and we hugged. There was something very raw and powerful about what we had just accomplished together. He was tearing up, as his emotions got the better of him. Perhaps he was overcome by an enormous sense of relief, or the beauty of the Tuolumne high country, as the sun’s last rays danced across the peaks. It might have been the reality that this would be one of our last climbs together, before he moves away to Oregon. A fitting end to this chapter of our lives, that’s for sure.

These were the thoughts that ran through my head, as we stood atop Fairview Dome.

The long day absolutely rocked us, physically. How some teams manage to do two or three routes like this back-to-back is unfathomable to me. Alex Honnold climbs the equivalent of 10 of these routes in a day, sometimes without a rope. Is he even human? We drove back to camp and chowed down on the homemade chili/bacon/cheese we brought and crashed for the night. I was too tired to drink beer. Our original plan was to climb Matthes Crest the next day – an even longer route with 10+ miles of hiking added in. Neither of us had to say a word; that wasn’t going to happen.

We slept in the next morning (best night of sleep ever) and spent the day touring the Valley, Joey’s first visit. We stared up at El Cap and visited Camp 4. We touched the starting holds on Midnight Lightning, the Yosemite testpiece that is still far, far beyond our ability level. One day, perhaps?

We flirted with the idea of backpacking in to the base of Matthes Crest that night, and even went as far as buying some food for the trip. The plan was to hike in, bivy at the base, and then climb the next day and hike out. I had to be back in San Diego by noon the following day, and it would be a super tight schedule (and very, very tiring). After waffling back and forth all afternoon, we ultimately decided to bail on the plan and save Matthes for a future trip. We were still rattled from our day on Fairview, and the thought of another long, exposed climb was unnerving. Instead, we climbed a fun route called Northwest Books on Lembert Dome, an old Warren Harding route that goes at 5.6. We did the 5.9 variation (Joey’s lead) which made it a bit more spicy, but the climb felt pretty casual and I was reminded why we were up there in the first place. It was a thoroughly enjoyable day on the rock. From the top of Lembert, we could see Cathedral Peak, Fairview Dome, and caught a glimpse of Matthes Crest. Clean, white granite poking out from the surrounding forest – it was impossible not to love this place.

On our rest day, I bought Zane a deck of Yosemite playing cards with pictures of all the major icons. He’s into playing war right now, and he likes rocks, so it made sense. The day after I got home, we played a few rounds of war (he can play for hours) and I pointed out El Cap, Half Dome, Yosemite Falls, and even Lembert Dome. “Look at this rock, Zbug! Daddy climbed this rock yesterday!” From the comfort of my living room, it was weird to think that I was standing on the top of that summit, just hours before. Zane nodded, but was more interested in the fact that he had a queen that beat my seven. He grabbed the card out of my hand and tossed it into his pile. Well, one day he will appreciate these photos, I thought to myself. He’s only three, after all.

The next morning, he came running over to me and asked me to follow him to the kitchen. He was really excited about something. “Look Daddy! It’s your favorite rock!” There, taped to the side of his little kitchen, was the playing card with the photo of Lembert Dome. I could have burst out crying, right then and there, I kid you not. In that silly little moment, everything important to me in life became so clear.