One of my climbing goals is to gain more experience on long traditional routes. These types of climbs involve the whole kit of skills; anchors and protection, rope-work, route-finding, endurance, and of course technical ability. Tahquitz is only two hours from home and an ideal venue for such fun.

Joey and I wanted to climb two routes: Fingertrip (5.7) and Left Ski Track (5.6). Given their respective locations, we opted to tackle the harder route first, which would allow us to cruise the easier climb at the end of the day, and on the way back from the friction descent. This turned out to be a good decision, but not for the reasons we planned.

We hiked to the base of Fingertrip and set our packs down. Another party had already started the climb, and we watched as the second made his way up to the first belay, at a big tree. No problem, since we were tired from the approach and it would give us a few minutes to relax and prepare ourselves for the 400 foot, 4-pitch classic above. A few minutes passed by and I was fumbling with my gear when I heard someone from high above yell “ROCK!!” Startled, we both turned our heads towards the sky. Nothing. Then, a second or two later, something comes whizzing from directly above and slams into the rock immediately to Joey’s side. Literally inches away. HOLY SHIT! The moron above had just dropped his ATC-Guide and it very nearly detonated onto Joey’s skull. After last year’s rockfall incident, I was paranoid about boulders falling from the sky, but apparently climbing gear would be today’s danger. We quickly donned our helmets.

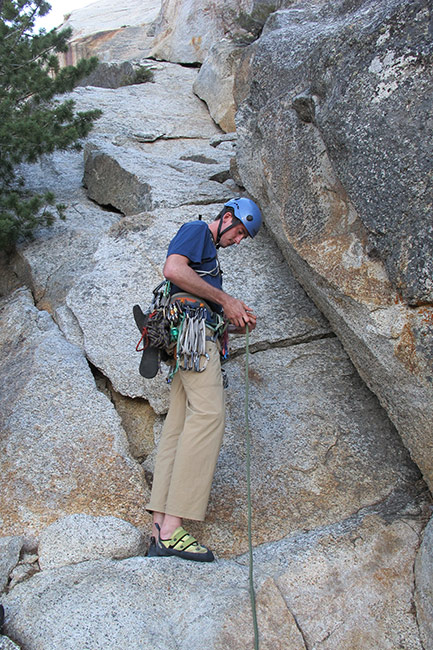

Joey decided to lead the first pitch, since we knew it would end at a tree, which would make for an easy, secure anchor. This being his first trad multi-pitch, the prospect of a tricky gear anchor left both of us feeling nervous. Before starting, he took a few bites out of his shoe, which has apparently become a pre-climbing ritual. Actually, I think he was just blowing rocks out from the insides.

The first pitch was fairly sustained, 5.7 climbing up a left-facing dihedral (165 feet). After ~80 feet, Joey turned a corner and he went out of view, following a lieback-finger crack to the top (5.8 according to the Gaines guidebook). A bit later, he called off belay and I got ready to follow. By this point, there were two other parties waiting behind us, and I wanted to climb fast and efficient. Partly, so that we wouldn’t appear to be gumbies, but also so that we’d have plenty of time and energy left for the Ski Track.

We encountered the first snafu before I left the ground. Joey had me on belay and thought he had pulled the rope tight, but in reality I was standing at the base with nearly 10 feet of slack. Lots of rope drag, or it must have been stuck behind a feature. I waited and I tried shouting a couple of times, but it was difficult to hear each other. I started up the easy blocks, essentially free-soloing as I watched a big loop of slack collect below my feet. I pulled on the rope a few times to see if it might be caught on something. Thankfully, Joey must have heard me yelling, “Up Rope!” because it finally came tight on my harness. After pulling the corner, we could finally communicate, and I told him I was impressed with the sustained nature of the route. It felt pretty stiff for a 5.7 and I was glad to be on top rope. It also occurred to me that I would be leading the next pitch, and I shook off a wave of doubt.

I reached the tree and clipped into the anchor, we exchanged gear, and I began the next pitch by heading straight up some large blocks. This is where the second snafu occurred. You see, I was carrying my iPhone with all the route topos and a bunch of pictures, because I am always worried about getting off-route on a committing climb like this. However, we had two groups of people breathing up our asses and I didn’t want to dilly-dally. In my haste, I must have climbed straight up and past the cracks that angle left, effectively skipping the second pitch and venturing out onto unknown territory (unbeknownst to me). I was looking for a left-facing arching roof, and I saw one up above. Wrong roof. Anyway, after mulling my options for some time, I decided to commit to the surprisingly blank slab ahead and to the right. I think I knew I was going off route, but the alternative looked completely void of protection. What I should have done is down climb back to the belay to investigate the options down low, but every time I looked down I saw a bunch of people staring up at me, and I felt like I had to get moving. In the future, to hell with them. We got there first and they will just have to wait.

I made some insecure moves across a rounded arete and onto the slab, and I really didn’t know if there would be any options for protection. I could see the start of the arching roof about 30-40 feet above, and all I had going for me was some confidence that I could pull through this section without falling, if it really came down to it. Thankfully, as I moved higher up the slab, I did find a few places for pro. I aimed for a thin crack with a single, rusty piton and by the time I reached it, I was feeling pumped and pretty uncomfortable. It was the same feeling of “focused jitters” that I’ve gotten on a couple other climbs (always with Joey on belay, it would seem). I wasn’t thinking about the grade, or the pump that was building in my hands and feet. I was entirely focused on reaching that damn roof, where good pro would certainly await.

I made it, and the climbing immediately eased off (back to 5.7 territory). I felt so much better with a few solid pieces below me, but I was still in a terrifically exposed spot and holding on by under clinging and stemming out from under the roof. Now I was worried about logistics, because I had run out of slings, was low on gear, and feared I was close to the end of the rope. I debated whether I should traverse another 25 feet to a little ledge, or just build a hanging belay right then and there.

I down climbed back to my last bomber piece, a big nut that I had wedged into a little notch behind the flake. I felt really good about that piece. Then I climbed up a few feet and sank a blue Camalot, and I found another big stopper placement just above that. As I stood there, clinging to this exposed flake, I couldn’t believe that I was actually building an anchor at such a precarious position. Oh well, after spending all this time practicing my rope-anchor rigging, I have to admit that I was satisfied to use the technique in precisely the sort of situation for which it is suited. I had to pull a lot of rope since the top-pieces stretched out past arm’s reach, climbing up and down to tie the cloves and equalize the whole rig. It looked solid, and I finally felt (somewhat) secure. I put Joey on belay and brought him up.

The smile on Joey’s face was somewhat satisfying, as I watched him negotiate the crux moves past the piton and up into the flake. He told me they felt like .10a moves, which is a lot harder than either of us had bargained for, on this supposedly mellow climb. I could also tell that he wasn’t enthusiastic about our hanging belay, and he quickly led off on the next pitch, which traversed 25 feet to a much safer ledge. Before leaving the belay, he was able to place a couple of cams under the flake, which served to reduce the risk of a catastrophic belay-ripping fall. Once he made it to the ledge, I let out a sigh of relief. We might have been off route, but at least we had negotiated the tricky parts. Now that I’m able to examine the topos from the comfort of my home, it appears that we deviated from Fingertrip and crossed over some unnamed slab, eventually linking up with the upper part of Fingergrip (5.8). It was a spicy and fun experience, and I suppose the sort of thing that one must be prepared for when climbing at Tahquitz.

I joined Joey at the third belay and we appeared to be very close to Lunch Ledge. If true, this would mean one final pitch of easy climbing to the top. I led off and crossed Lunch Ledge (much to my relief) and headed up broken ledges towards the friction slab at the top. I slung my pieces long and ran it out to avoid rope drag, and eventually made it to the final crack that marks the start of the slabs. I clipped a fixed hex and backed it up with a purple C4, and then started up the slab towards a single bolt, about 20 feet above. The slab here is rated 5.4, but it felt just as hard and nearly as committing as Stitcher Quits (5.7) in Joshua Tree. I was dealing with quite a bit of rope drag at this point, and add to that some gusts of wind, and I was pretty jittery as I climbed towards that lone bolt. Falling here would not be pretty.

In the mean time, Joey was sitting at the belay and watching nervously as our rope dwindled away towards it’s end. As it turns out, I pulled the last bit of rope just as I topped out, and he was freaking out below as I walked around trying to find a good spot to belay from. He held onto three feet of slack as a sort of insurance measure (insurance against what, I’m not sure) and was worried that I might be halfway up the slab, unable to move. That would have truly been a nightmare. But I was relatively safe on top, and even though I couldn’t reach the best belay point, I situated myself near a car-size boulder and built a 4-piece anchor, belaying Joey directly from my harness. The top out on Fingertrip was significantly more difficult than what I experienced on The Trough.

We were both feeling pretty beat by this point. The climb had taken much longer than expected due to my route-finding error. We scrambled up the slabs to the start of the friction descent and wound our way back to our packs, passing Left Ski Track on the way. The climb looked great, but it was clogged with a slow party of three, and we decided to eat some food and call it a day.